There was no family history of Huntington's disease in Gemma's family until they discovered the expanded gene.

Gemma's family story is rarer than rare but it is important to share as this is her journey navigating the unknown. Gemma's grandad had a copy of the Huntington's gene which was in the grey area. He did not have symptoms but there was a very small risk that he could pass on the disease. There is limited information about the grey area so it helps us to delve deeper into Huntington's genetics and gene expansion.

To make it easier to understand, throughout the blog we have added in some explanations in bold.

Genetics and the grey area

Everyone has two copies of the Huntington's gene - one inherited from each parent. If you have been through genetic testing you will know that you get two CAG repeats results which often look something like this:

- 24,18 - both inherited genes are in the normal range and the person will not develop Huntington's

- 17, 40 - the person has inherited the normal gene from one parent but the expanded gene from the Huntington's carrying parent

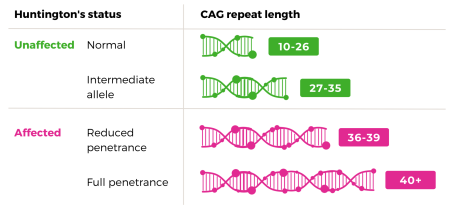

There is also a range of expanded genes that fall into the 'grey area' this is between 27 and 39. We will explain these in further detail later in the blog.

In January 2011 my mum Hilary was diagnosed with Huntington’s disease at the age of 51. I was 15 at the time. My mum is now 64 and is in the end-of-life stage of Huntington’s.

Mum had been experiencing worsening involuntary movements (chorea) for a few years prior to being diagnosed, but in hindsight she had other symptoms that started several years prior to the chorea beginning. However, she was diagnosed late due to having no family history of Huntington’s disease.

Before Huntington’s changed my mum’s brain, she was the most loving and compassionate person you could wish to meet. She was unconditionally kind and gentle, would do anything for anyone, and loved every living being on the planet. Everyone she met loved her, and she loved everyone she met. So when she started to change, it was scary for us.

Mum’s first symptoms were depression, anxiety, obsessive thoughts and becoming easily frustrated, but at the time she was told by the GP that they were symptoms of menopause. But as I started to see my friend’s parents going through the menopause, I began to worry that there was something more sinister going on. By this time Mum’s personality had started to change, and she struggled with hallucinations, paranoia, mood swings, and was often stuck on the same subjects or sentences, repeating them again and again. Then the chorea started to creep in, with small facial twitches at first which then became bigger movements throughout her entire body. Work became increasingly difficult and she struggled to plan, coordinate, motivate herself, and complete household tasks. She had started to become aggressive towards us, sometimes shouting, hitting out or throwing things.

No family history

Eventually, Mum’s GP referred us to a neurologist to investigate her chorea. As there was some uncertainty around the cause of Mum's symptoms, she was admitted to St George’s Hospital for a few days for tests and an MRI. After this, it was confirmed that Huntington’s disease was the most likely diagnosis. Mum immediately agreed to have the genetic test.

For our family Huntington’s disease happened 'out of the blue'. This was due to one of my grampa's CAG repeats being in the intermediate allele range. This had not caused any symptoms for him, but had then expanded when it was passed on and caused symptoms in my mum. We discovered that this expansion is much larger than average, making my mum a very rare case.

The gene that causes Huntington’s is often called the huntingtin gene (HTT). It produces an important protein, called huntingtin, which is needed by nerve cells in the brain (neurons) and for the body’s development before birth.

The gene responsible for causing Huntington’s disease is the huntingtin gene (HTT gene) and everyone has two copies of the HTT gene (one from both parents). Huntington’s disease is caused when there are mutations (otherwise known as expansions) in the HTT gene.

When Mum was initially diagnosed with Huntington’s with 17 CAG repeats (normal range) and 45 CAG repeats (full penetrance) it was a complete surprise as we had no known family history, and my Grandma and Grandpa were in their late 80s by this point and had no symptoms of Huntington’s disease.

My mum has two sisters, who both decided to have genetic testing after my mum’s diagnosis. One of Mum's sisters tested in 2011, immediately after my mum received her results and her CAG repeats were 17 and 19 - both within the normal range (10-26).

Mum’s second sister tested in 2015. Her CAG repeat was 17 (normal range) and the other was 29 (intermediate allele). This meant that one of her HTT genes had expanded slightly into the intermediate range. We were told that this wouldn’t cause her to develop Huntington’s disease, but it could have implications for her children.

The grey area is a rare diagnosis. Part of the grey area is unaffected by Huntington's status and part is affected.

The higher end (36-39 CAG repeats) is known as 'reduced penetrance'. This means the person may or may not develop the disease but if they do it will be much later in life.

If a person has between 27 and 35 CAG repeats it is known as 'intermediate allele'. The carrier of a gene in this range will not develop Huntington's disease but this gene does have the ability to expand (CAG repeat number can increase) when passed down to the next generation. This means that the child could either have the same CAG repeat and also be in the intermediate allele range or an increased number which would mean they could go on to develop Huntington's disease.

The beginning of the investigation

At this point the plot started to thicken, as the numbers weren't adding up in the way that the genetics team had expected. A few possibilities were raised, one of which was that my mum might not have the same father as her sisters. But we doubted that paternity was an issue, because all three sisters look very much alike and have traits from both my Grandpa and Grandma.

It was around this time that St George’s Hospital in London collaborated with North York General Hospital in Toronto, and a team effort was made to find out more information.

We then had to make the difficult decision to tell my Grandma about mum’s diagnosis. By this time, she was 91 and although she was incredibly healthy for her age, we were all worried about how she would cope with the news, especially because my Grandpa had passed away earlier that year and the timing wasn’t ideal. But when my mum’s sister told her about the situation, Grandma surprised us all by taking it all in her stride, and readily insisting on being tested herself so that she could help the family. It must be completely devastating to find out so late in life that your daughter has an incurable, genetic neurodegenerative condition but she was determined to help future generations however she could. Grandma had the genetic test in December 2015. Thankfully, she received a normal genetic test of 17 and 17 CAG repeats.

At this point, we had to assume that it was Grandpa who had carried the faulty gene. With the help of Mum’s sister, the genetics team in Toronto were able to obtain a DNA sample posthumously from Grandpa, via a sample of cheek cells that were still in storage after being sent off for to direct-to-consumer genealogy DNA testing many years ago.

Test results

The sample was shipped to St Georges in London, where the genetics team carried out genetic sequencing on the cheek cell and discovered that my Grandpa’s results were 19 and 29 CAG repeats, with one normal allele, and one allele that had expanded into the intermediate range. This explains why he didn’t have any symptoms himself, but was able to pass Huntington’s disease on to my mum.

Through allele sizing and linked markers, the genetics team were able to ascertain that the intermediate allele (29 CAG repeats) was inherited from my Grandpa. This means that there was an expansion of 29 to 45 over one generation, which is rare. At the time, this was believed to be the first published case ever recorded of this happening.

We now know that my mum was definitely the first person in our family to have Huntington’s. Although it's hard to understand how this can happen, it makes sense when you consider that it has to start somewhere.

We believe that our family’s story shows the importance of offering genetic testing to individuals whose parents are in the intermediate allele range. Access to this kind of testing is so important, and it’s not available everywhere. We are incredibly grateful to both of the incredible genetics teams involved in our family’s case, who have provided follow-up genetic counselling and testing to those members of our family who were affected by this result and wanted to consider testing themselves. It has opened up genetic testing to my cousins, who would otherwise never have been able to know their own genetic status and would have had to live in fear of passing on Huntington’s disease to their children.

St George's Hospital case report

When my mum’s case study was first published, it was believed to be the only known case of a single step Huntington’s disease transmission from 29-45. We were asked whether we would be happy for our family’s story to be published as a case study, and we didn’t need to think twice before agreeing to this. If it helps to improve our understanding of Huntington’s disease, then it's worth it. We’ve been on quite a journey since 2010, from knowing nothing at all about the disease, to being dropped into the deep end and being propelled into raising awareness of Huntington’s however we can. As one of my mum’s sisters says, “as a family we have to do whatever is necessary to steer Huntington’s disease towards a cure”.

My mum’s genetic backstory makes her rare within the rare. Not only does she have a rare genetic disease, but she has also inherited it in a very rare way. And I think that makes it especially important for me to talk about our story. There probably aren’t many people in the world who are children of parents who have inherited Huntington’s disease in this way, so I feel that it's my responsibility to talk about it.

We spoke to Consultant Clinical Geneticist, Nayana Lahiri who worked on this case. Below is what she had to say about Gemma's family story.

It is never easy to come to terms with a diagnosis of Huntington’s disease, even more so when there isn’t a family history of the condition. Intermediate alleles are present in 6-8% of the general population; they don’t cause Huntington’s disease in those people and they are usually stable. They do not all come with a high risk of expansion into the range that causes Huntington’s disease. Therefore when large expansions happen from an intermediate allele, like in Gemma’s family, there are lots of unanswered questions that can be really challenging for families like them and also those that are trying to support and advise them. There are lots of Huntington’s scientists trying to figure out why some CAG repeats are unstable and potentially how to prevent expansions from happening which might help us to answer some of the questions in the future.

Genetics information

If you would like more information about the genetics of Huntington's disease, you can find out more below.